2026 New Year Brief |Innovation as Strategy in an Age of Systemic Competition

As the world enters a new phase of global transformation, science, technology, innovation, and artificial intelligence (STI/AI) have moved decisively beyond the realm of economic development policy. They now sit at the core of national strategy, shaping how states organize power, manage risk, sustain legitimacy, and position themselves within an increasingly fragmented international system.

The past decade has witnessed the proliferation of national STI and AI strategies across major economies. From China’s articulation of science and technology as a foundation of national rejuvenation, to the United States’ security-inflected innovation governance, the European Union’s rule- and values-based approach, South Korea’s coordinated industrial upgrading, India’s scale-driven digital ambitions, and Qatar’s knowledge-economy diversification efforts, these strategies reflect far more than technical priorities. They reveal how states interpret the future, assess uncertainty, and recalibrate their long-term trajectories amid geopolitical tension, technological disruption, and environmental constraints.

However, public discussion of STI strategies often remains fragmented—treated either as economic planning, industrial policy, or technology governance. What is frequently missing is a strategic intelligence perspective: an approach that reads these strategies not only for what they propose, but for what they imply about national intent, coordination capacity, risk tolerance, and systemic ambition.

National STI strategies now define the “rules of engagement” of global competition. States are revealing not only what they want to build—but what they are willing to protect, trade off, or abandon. Drawing on a comparative analysis of formal national STI and AI strategies across China, South Korea, India, Qatar, the United States, and the European Union, the analysis applies an integrated strategic framework that connects four analytical layers of Meta-Geopolitical Capacities for Qualitative and Innovation-driven Growth :

... explores how the Fourth and Fifth Industrial Revolutions have reshaped the economic and political landscapes, emphasizing the importance of technological advancement, cross-sectoral collaboration, and multi-stakeholder synergy through the expanded Quintuple Helix model...

(1) meta-geopolitical capacities that define national power and resilience;

(2) governance architectures that determine coordination and execution;

(3) industrial competitiveness logics shaped by sustainability and circularity; and

(4) entrepreneurship models that translate strategy into innovation practice.

As a New Year Brief, this analysis presents a strategic comparative analysis of national Science, Technology & Innovation (STI) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) strategies across nations. The selection of six cases is deliberate and analytically significant, as these cases collectively represent the typical spectrum of contemporary STI and AI strategy formation in the context of global systemic competition. China and the United States constitute the principal poles of technological and geopolitical rivalry, shaping global norms, supply chains, and security logics. The European Union represents a distinctive regulatory and values-based innovation model, exerting influence through standards, sustainability governance, and international rule-making rather than solely through technological dominance. South Korea exemplifies a highly coordinated middle-power strategy that integrates industrial upgrading, alliance positioning, and technological specialization. India illustrates a scale-driven and demographically anchored innovation trajectory with high growth potential but heterogeneous governance capacity. Qatar, as a small but capital-rich and diplomatically active state, offers insight into how emerging knowledge economies leverage targeted STI investment and international connectivity to compensate for structural constraints. Therefore, these cases enable a structured comparison across different sizes, governance systems, development stages, and strategic roles, allowing this study to identify how national STI strategies function as instruments of power, coordination, and long-term positioning within the evolving global order.

By combining innovation studies with intelligence analysis, capability assessment, intent inference, governance mapping, and strategic risk evaluation, this analysis clarifies how different systems pursue advantage through distinct configurations of power, values, institutions, and agency. In an era marked by fragmentation and rapid technological change, the ability to interpret STI strategies as instruments of global strategy is no longer optional—it is essential for more informed dialogue, deeper comparative understanding, and a renewed appreciation of innovation as a central arena of global strategic interaction.

Introduction Across Major Strategic Actors

People’s Republic of China

China frames scientific and technological advancement as a foundational strategy for national rejuvenation and China’s long-term development vision. Since the 18th National Congress in 2012, China’s leadership has prioritized an innovation-driven development strategy and established the goal of building China into a country strong in science and technology by 2035, positioning science and technology as core drivers of economic strength, national security, and comprehensive national power.

At the heart of the strategy is an emphasis on strategic science and original innovation. China highlights breakthroughs in basic and frontier research—spanning quantum technologies, life sciences, materials science, and space science—as evidence of progress, while acknowledging that China still needs to strengthen its capacity for original scientific contribution and high-end innovation. It underscores a conscious shift toward measures to foster world-class research capabilities, including deeper structural reform of science and technology management, international cooperation, and the cultivation of high-caliber scientific talent.

Strategic science is further defined as both foundational and forward-looking. The speech delivered by President Xi in 2024 advocates:

Striving to Build a Country Strong in Science and Technology

- advancing basic research and theoretical discovery,

- achieving breakthroughs in core technologies that underpin key industrial and security domains,

- expanding China’s influence and leadership capacity in global science and innovation,

- building strong scientific talent pipelines, and

- strengthening governance systems to support efficient, coordinated scientific effort.

In essence, China positions strategic science as a national priority tightly integrated with economic, security, and societal goals. It calls for targeted investment in critical areas such as integrated circuits, AI, next-generation information technologies, advanced materials, and biotechnology—while promoting greater coherence between education, research, and industrial application to sustain long-term innovation capacity. China's push to become strong in science and technology within the broader systemic context of the global scientific revolution and international competition, asserting that frontier technologies such as AI, quantum science, and biotechnology are reshaping the global order and that China must rapidly deepen structural reforms to fully mobilize innovation resources and personnel. It outlines a dual approach combining unified Party leadership with market mechanisms, enhanced coordination across universities, enterprises, and research institutes, reform of evaluation and governance systems, and expanded openness to international cooperation while balancing self-reliance—emphasizing that cultivating talent, supporting enterprise-led innovation, and strengthening global scientific partnerships are essential to achieving the 2035 strategic objective.

Republic of Korea

South Korea has developed a comprehensive pan-government national strategy to nurture strategic technologies, directed at securing economic competitiveness and technology sovereignty. This plan involves:

- A National Science Technology Advisory Board chaired by the President to set strategic priorities across government, academia, and industry.

- Identification of 12 National Strategic Technologies (e.g., 5G, quantum computing, AI, advanced manufacturing) with targeted R&D investment and policy support.

- Legislation such as the Special Act on the National Strategic Technology to institutionalize governance, R&D incentives, talent cultivation, and international cooperation.

AI and Innovation Ecosystem Plans

In 2025, South Korea established a National AI Strategic Committee as a central policy coordination body, aiming for the country to become a top-three global AI power with an AI innovation ecosystem, data infrastructure, and national transformation goals.

Research Funding and Policy

Recent government announcements outline significant increases in research spending focused on AI, advanced computing, and strategic industries, reaffirming long-term innovation priorities.

Comparison with China

While South Korea’s strategy is more formalized in plans and institutional frameworks rather than a single national speech, it similarly prioritizes strategic technologies and innovation for national competitiveness, linking policy design with economic and security concerns.

United States

National Security Strategy (2025)

The U.S. 2025 National Security Strategy articulates a broader national interest framework. It emphasizes the foundational role of science, technology, and innovation in national power and security (e.g., maintaining leadership in critical emerging technologies). . It emphasizes

National AI and R&D Plans

The U.S. government (e.g., White House via America’s AI Action Plan and its National AI R&D Strategic Plan) has released formal AI strategy documents that guide federal research investments, innovation infrastructure, and adoption across sectors.

These plans include:

- A focus on accelerating AI research and adoption.

- Coordination across federal agencies and with the private sector.

- Emphasis on maintaining global leadership through market-driven innovation.

Standards and Critical Emerging Technologies

Entities like NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) provide strategic priorities for U.S. leadership in critical and emerging technologies (e.g., AI, quantum, biotech, semiconductors).

Comparison with China

The U.S. approach is more decentralized and market-driven, with government frameworks guiding rather than centrally directing all aspects of science and technology. It is formalized through policy documents, executive orders, legislation (e.g., Innovation and Competition Acts), and agency strategic plans rather than a central “nation-building” speech.

European Union

EU Strategy on Research and Innovation

The European Union has an overarching Strategy on Research and Innovation that outlines how research and innovation will:

- Support digital and green transitions.

- Strengthen European sovereignty in digital, data, and innovation sectors.

- Promote economic and societal resilience and global engagement.

European Strategy on Research and Technology Infrastructures

In late 2025, the European Commission adopted a long-term strategy focused on building world-class research and technology infrastructures, facilitating access for researchers, attracting talent, and strengthening international scientific collaboration.

Comparative Nature

The EU’s strategy is policy-document-based and institutionalized through multi-annual programming (e.g., Horizon Europe), and is not delivered as a single speech but is strategically integrated into legislative and budgetary frameworks.

Qatar

Qatar National Vision 2030

Qatar’s long-term development framework — Qatar National Vision 2030 — provides broad strategic guidance for economic diversification, human capital development, and knowledge economy goals, which imply the importance of science, technology, and innovation as underlying drivers.

Character of Qatari Strategy

Qatar’s science and technology strategy tends to be embedded within broader national planning frameworks and sector-specific strategies rather than in standalone high-profile speeches — but it serves similar purposes by guiding national innovation goals.

India

India’s national approaches to science, technology, innovation, and AI encompass several complementary policies:

National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence (2018) — initially framed under NITI Aayog, this strategy emphasizes using AI to address development challenges and promote AI for All. It prioritizes AI applications across health, agriculture, education, and infrastructure while building foundational research and innovation capabilities.

IndiaAI Mission & Governance Framework (2025) — India’s updated AI governance guidelines adopt a “light-touch, risk-based” approach that balances innovation with ethical, transparency, and accountability principles. This complements India’s digital ecosystem and national priorities like Viksit Bharat (Developed India).

Science, Technology & Innovation Policy (STIP, 2020) — this broader STI policy aims to strengthen India’s innovation ecosystem by connecting academia, industry, and government, supporting mission-mode R&D projects, and nurturing global competitiveness.

Primary goals. Use AI to solve societal challenges; build robust digital public infrastructure; democratize AI access; and promote innovation with ethical safeguards.

Although differing in institutional design, emphasis, and governance approach, these STI and AI strategies share a common purpose: to mobilize science and technology as foundational drivers of national resilience, competitiveness, and geopolitical influence. Each actor’s strategy provides insight into how innovation policy is being reconfigured as both an economic engine and a strategic instrument in a contested global landscape.

Comparative Analysis of Global STI and AI Strategies

The comparison also provides actionable insights into how STI strategies function as early indicators of geopolitical behavior, alliance formation, and systemic risk. As such, the analysis contributes not only to academic debates on innovation systems but also to strategic foresight, policy intelligence, and global governance discussions at a time when technological capability has become a decisive factor in international competition and cooperation. This comparative analysis offers a horizon-scanning perspective on how these regions design STI/AI policies as instruments of economic competitiveness and geopolitical strategy.

Meta-Geopolitical Capacities in National STI Strategies

National STI strategies are increasingly designed to enhance broad meta-geopolitical capacities – the foundational strengths that enable countries to compete and thrive. The comparison above illustrates that while all six actors recognize STI and AI as comprehensive strategic tools, they modulate their strategies to national contexts. For instance, social & health objectives are prominent in India’s and the EU’s plans (emphasizing inclusivity and public welfare), whereas China and South Korea – though also concerned with societal well-being – more explicitly frame tech innovation as a response to demographic changes (aging) and a means to improve social services efficiency. Political capacity (in terms of governance and autonomy) is a driving force in China’s and India’s self-reliance narratives, and in the EU’s quest for unity and strategic autonomy, whereas Qatar leverages STI mainly to reinforce its national vision and stability in a volatile region. The economic dimension is a common thread – all strategies are fundamentally aimed at growth and competitiveness – yet their approaches differ (e.g., the U.S. and EU rely more on private sector dynamism and market mechanisms, while China and Qatar lean on state-guided investments and plans). On environmental capacity, the EU stands out for embedding sustainability across its entire innovation agenda, essentially marrying green goals with industrial policy. In contrast, other countries still treat it as one priority among many (albeit growing in importance). For science and human potential, we see divergence in talent strategies: the U.S. and EU bank on attracting global talent and open science, China is rapidly building its domestic talent pipelines, and India and Qatar focus on education reforms and international partnerships to develop human capital. The military/security aspect is most pronounced in the U.S., China, and (to a lesser extent) India and Korea – linking STI to defense is a priority for the major powers, while the EU is cautiously stepping into defense R&D, and Qatar remains focused on internal security tech. Finally, in international tech diplomacy, all six recognize that leadership in STI confers global influence: the U.S. and EU currently set many of the norms, China is asserting itself with an alternative vision, and middle powers like India and Korea collaborate to amplify their voice in governance forums.

Notably, these capacity areas are interconnected, and differences emerge in how holistically the strategies address them. China’s and South Korea’s plans are perhaps the most integrated, linking scientific advancement to economic growth, social programs, and military strength in a unified narrative. India’s strategy is highly inclusive, socially and politically (bottom-up formulated), but faces challenges in execution across such a vast system. The U.S. has strong capabilities in each dimension but often treats them in parallel (e.g. separate initiatives for defense, climate, etc., coordinated loosely by OSTP). The EU’s strategy is comprehensive in principle (covering all seven dimensions across its policies). Yet, implementation depends on member states’ uptake – leading to strengths in environment and diplomacy, but persistent gaps in defense integration. Qatar’s strategy, while ambitious, must compensate for its small scale by heavily leveraging international scientific cooperation and a focused set of priorities (energy, health, etc.). These nuances underscore that a nation’s innovation strategy reflects its broader geopolitical circumstances and goals: STI is not developed in a vacuum but is explicitly harnessed to bolster national power and address perceived vulnerabilities.

Helix Governance Architecture and NGNI Alignment

A second analytical lens is the helix governance model, which assesses how well each strategy aligns multi-helix actors – government, industry, academia, and civil society – in a cohesive innovation ecosystem. An “NGNI-aligned” strategy involves not just the National government vision and Governmental agencies, but also Networked partnerships and Institutional (non-governmental, non-industrial) actors. We examine patterns of integration or fragmentation in each context:

China

China’s innovation governance is centralized yet broad-based. The national strategy is set at the highest level (the CPC Central Committee outlines S&T in the Five-Year Plans), ensuring a strong National directive. Governmental coordination is enforced through initiatives like the “whole-nation” R&D system which mobilizes ministries, local governments, and state-owned enterprises toward strategic tech goals (for example, multiple ministries jointly implement the AI Development Plan). Networked collaboration exists but is often state orchestrated: industry and academia are pulled into national mega-projects (e.g. semiconductor self-sufficiency) via funding programs and administrative guidance. Top tech firms are designated as “national champions” and expected to align with state goals (e.g. Baidu leading a national autonomous driving platform). Institutional involvement beyond industry – such as universities and research institutes – is significant, as China has expanded R&D at its universities and the Chinese Academy of Sciences; however, NGOs or civil society have a relatively minor formal role (apart from providing some science popularization), given the tight party-state control. Integration is high between government, academia, and industry (often through joint labs, talent programs, and public-private funds), but the model is top-down: the central government steers the helix, which limits bottom-up initiative from non-governmental actors. This approach has yielded clear direction and rapid mobilization (as seen in big projects like the Moonshot for AI chips), but it risks fragmentation along different lines: bureaucratic overlap and regional duplication can occur when everyone is tasked to innovate, and private creativity may be tempered by state oversight.

South Korea

Korea’s STI governance epitomizes Triple Helix collaboration (government–industry–academia) with increasing inclusion of a fourth helix (civil society where relevant, e.g. public engagement in consensus forums). The National level provides a guiding vision (the Master Plan, national AI strategy) which was notably formulated via an inclusive process involving all ministries and about 120 experts from industry, academia, and research institutes. This joint formulation indicates strong Governmental coordination – the existence of bodies like the Presidential Advisory Council on S&T (PACST) ensures ministries and agencies execute the plan in a synchronized manner. To break silos, Korea restructured its governance – for example, the presidential Fourth Industrial Revolution Committee was refocused into an AI-focused committee, chaired by the President, to oversee cross-ministerial AI policy. On the Networked front, South Korea actively involves the private sector and academia in implementation: there are public-private consultative groups so that industry needs feed into R&D programs, and major firms collaborate with universities on research (often co-funded by government). Specific policies support network integration, such as innovation clusters in regions (where local government, universities, and SMEs cooperate on specialized technologies). Institutional alignment is seen in how universities are being nurtured as research hubs and government research institutes (GRIs) given clear missions to avoid redundancy. Korea also solicits citizen input for agenda-setting (public hearings on the S&T plan) and addresses societal acceptance (e.g. an AI ethics framework with civic input). The overall pattern is one of integration: a relatively small country forging tight collaboration between government, industry, and academia. If any fragmentation exists, it might be between large conglomerates and smaller firms or between central and local innovation agendas – which the government is trying to mitigate by new coordination meetings and regional STI strategies. In summary, Korea’s helix governance is highly aligned, with robust institutions (MSIT ministry, PACST, etc.) connecting the helices, which has been credited with efficient execution of initiatives like its COVID-19 tech response and semiconductor R&D programs.

India

India’s STI governance has historically been government-centric, but the latest policy efforts strive for a decentralized, inclusive helix. The formulation of the 5th National STI Policy was unprecedentedly “Bottom-up, Decentralised, Experts-Driven, and Inclusive” – featuring nationwide public consultations, thematic focus groups, state-level consultations, and engagement with NGOs and industry. This participatory approach indicates a strong attempt to incorporate Networked input (from experts, private sector, and civil society) at the agenda-setting stage. In practice, however, implementation still relies on National and Governmental mechanisms: India has multiple agencies (Department of Science & Tech, Principal Scientific Adviser’s office, NITI Aayog for AI, etc.), and coordination among them can be a challenge. The STI Policy calls for creating an overarching STI Governance framework and perhaps a unified authority to align efforts, as well as STI units in each ministry and state government – a recognition that fragmentation exists across ministries and between central and state levels. Progress is being made: for example, the Empowered Technology Group (ETG) under the PMO helps coordinate emerging tech decisions across ministries, and the National Education Policy ties into STI goals, linking institutions. On the Institutional side, India boasts a vast network of national research labs, universities, and increasingly start-up incubators (often hosted at academic institutions). The new policy envisions an “institutional architecture to integrate Traditional Knowledge Systems and grassroots innovation with the overall research and innovation system”, which would bring community-level innovators into the helix formally. Industry’s role is growing through initiatives like public-private partnerships (e.g. the Semiconductor Mission inviting private fabs with govt incentives) and a government fund-of-funds for start-ups. Civil society and the general public are also drawn in for scientific temper and policy input – India conducts citizen science projects (like biodiversity apps) and has consultative bodies including NGOs for ethical debates (e.g. on AI in policing). Despite these efforts, fragmentation remains a challenge: funding is dispersed and often bureaucratic, and academia-industry links are weaker than in more developed systems (the policy explicitly aims to improve that). Nonetheless, India’s trend is towards greater alignment: e.g. missions like the vaccination program involved government labs, private pharma, and community outreach in tandem, showcasing a successful multi-helix mobilization. The hope is that new governance reforms (like the forthcoming National Research Foundation to coordinate research grants) will institutionalize a smoother helix integration going forward.

Qatar

As a small, centrally governed nation, Qatar’s STI governance is highly centralized but partnership-oriented. The National vision (Qatar National Vision 2030) provides top-level direction, and under it the Qatar Research, Development and Innovation (QRDI) Council acts as the principal Governmental body steering STI. The QRDI Council’s strategy was formulated through “extensive collaboration and consultation” among its members, many of whom come from academia (Qatar Foundation, etc.) and industry, indicating multi-helix input at the leadership level. Qatar explicitly embraces a “golden triangle” of government, industry, and academia as the foundation of its RDI ecosystem. For instance, Education City (with its cluster of international universities) interfaces with industries (through Qatar Science & Technology Park) under government funding – a clear triple helix model in a microcosm. The Networked aspect often involves international partnerships: Qatar leverages foreign institutions (universities, companies) as part of its innovation network, essentially importing expertise and collaborating on research. Institutional actors like NGOs are fewer (Qatar’s civic sector is limited), but entities like the Qatar Scientific Club or civil society groups in areas like environment do exist and can feed grassroots innovation ideas (though on a small scale). The government also encourages public engagement in science (for example, through science festivals and grants for youth innovation projects) as part of building a culture of RDI. Coordination is eased by Qatar’s size – key players are relatively few and often interconnected via the Qatar Foundation or the government. This means alignment is generally strong: initiatives (e.g. a new AI program) can be rolled out across ministries, academic bodies, and industry with high-level patronage ensuring cooperation. A potential weakness is over-reliance on centralized decision-making: if priorities are set from the top, some network actors might be passive. However, Qatar is mitigating that by setting up platforms like Qatar Open Innovation to solicit challenges from industry and invite global solvers. In sum, Qatar’s governance architecture is integrative, leaning on public-private-academic partnerships often facilitated directly by state-led institutions, with minimal fragmentation due to its cohesive vision and scale.

United States

The U.S. innovation system is highly decentralized and network-driven, with partial coordination through federal strategies. There is no single “national STI plan” akin to a five-year plan; instead, the White House (OSTP) periodically issues strategy documents and coordinates via the NSTC, but much decision-making and funding is distributed across multiple agencies (NSF, DoD, NIH, DOE, etc.), state governments, universities, and private firms. This fosters a vibrant Networked ecosystem: universities and industries collaborate organically (e.g. Silicon Valley emerged from a dense network of Stanford University, startups, venture capital, and federal research contracts). The National level provides broad priorities – for example, OSTP’s annual science budget priorities memo, or the new requirement for a quadrennial National Science & Technology Strategy by Congress – but it does not dictate specifics to the same extent as a centralized plan would. Governmental coordination exists in pockets: the NSTC subcommittees align federal agency efforts on specific topics (e.g. the Select Committee on AI brings together agencies to develop a cohesive federal AI R&D plan), and multi-agency initiatives (like the National Nanotechnology Initiative) create cross-cutting programs. Still, fragmentation can occur when agencies have overlapping or even competing programs. Efforts like the creation of ARPA-H (a new health advanced research agency) are intended to break silos by borrowing DARPA-like models. On the Institutional side, the U.S. heavily involves academia and nonprofit institutions in STI – universities perform a significant share of fundamental research (with autonomy to pursue diverse topics), and NGOs or expert bodies (e.g. National Academies of Sciences) frequently advise on policy. Industry is the dominant force in later-stage innovation; the government often takes a backseat after funding early R&D, allowing market competition to drive technology deployment. Civil society has a voice mainly through advocacy (e.g. civil liberties groups influencing AI ethics discussions) and through public comment processes on regulations. The U.S. innovation governance can be seen as organized chaos: a strong underpinning of networks and market mechanisms yields world-leading innovation outputs, but the lack of a single coordinating hand means priority alignment relies on soft coordination (e.g. agencies aligning to presidential memos) and the incentive structures of funding and regulation. A recent trend is the government using industrial policy tools (funding incentives in CHIPS Act, public-private partnerships for manufacturing institutes) to steer networks toward critical national goals, effectively trying to tighten the helix linkages in strategic areas without undermining the fundamentally decentral nature. In conclusion, U.S. STI governance is pluralistic and network-centric, excelling in harnessing diverse bottom-up innovation, though at times challenged by duplication and the need for mission convergence (which is addressed by initiatives like the Cancer Moonshot rallying multiple actors to a common mission).

European Union

The EU operates a multi-level helix – coordination is needed not only across different sectors (government, academia, industry, society) but also across member states. The EU-level strategy (e.g. Horizon Europe, Digital Strategy) provides a supranational National-level vision that complements national STI policies of member countries. Through the European Commission, Governmental alignment is pursued by encouraging national governments to adopt common goals (like the Digital Decade targets) and by co-funding programs. A prime example is the Coordinated Plan on AI which explicitly sought to “ensure that the EU acts as one” on AI, syncing national AI strategies with an EU-wide approach. Tools like the European Semester now include innovation indicators to nudge national policies. On the Networked dimension, the EU is a strong promoter of public-private partnerships (e.g. Joint Technology Initiatives in electronics, medicines, etc., where industry consortia work with EU and national funding). Cross-border networks are facilitated via instruments like EUREKA for industrial R&D collaboration and COST for research networking. Additionally, the EU involves Institutional and civil society actors extensively in policy-shaping: stakeholder consultations are mandatory in developing major initiatives, and bodies like the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) give societal groups a formal say. The Quadruple Helix (adding civil society to the triple helix) is embraced in programs that demand societal engagement (for instance, Horizon Europe’s missions require citizen involvement in design and implementation of R&I to ensure uptake and acceptance). The presence of NGOs in areas like digital rights influenced the GDPR and AI Act proposals. The complexity of the EU system does risk fragmentation: member states differ in their innovation capacities and may pursue their own agendas (e.g. national research funding far exceeds EU funding, and countries like Germany or France have their distinct priorities). To mitigate this, EU initiatives like the European Research Area (ERA) aim to reduce duplication and “align national and EU research agendas”. We see progress in things like the synchronization of COVID-19 research funding across countries and the joint procurement of innovative health solutions. In summary, EU STI governance is consensus-driven and integrative, knitting together multiple governments and stakeholders. Its strength lies in orchestrating large-scale collaboration (no single European country alone could have built CERN or Airbus), and in setting common standards that unify the market for innovation. The trade-off is that reaching consensus can be slow, and initiatives must accommodate diverse interests, which occasionally leads to diluted ambition or delayed implementation. Nevertheless, when alignment is achieved – as in the Galileo satellite program or the upcoming EU Chips Act (with collective investment in semiconductor fabs) – the EU demonstrates a powerful helix alignment spanning many nations, industries, and institutions.

Integration vs. Fragmentation

Summarizing patterns, China and South Korea exhibit high integration internally (strong central coordination, clear roles for academia and industry), with China being more top-driven and Korea more consensus/committee-driven. India is moving from a fragmented, government-dominated model toward an integrated one by decentralizing input and encouraging state and private involvement, but it remains a work in progress with coordination mechanisms still solidifying. Qatar achieves integration by virtue of scale and central authority, incorporating external partners to fill gaps; fragmentation is low internally but capacity is concentrated in a few institutions. The U.S. has a different paradigm: integration happens through market and network forces rather than centralized planning – a strength for creativity and a weakness for directing efforts; fragmentation is managed by occasional federal interventions and a unifying culture of innovation in academia-industry linkages. The EU represents integration across boundaries – a slow but steady alignment process creating a meta-helix of nations, which is a unique governance experiment; fragmentation here means uneven participation by member states, something addressed by structural funds and inclusive policy processes.

In all, effective STI strategies require aligning the multiple helices of innovation. Those that have achieved clarity of roles and collaboration mechanisms (e.g. South Korea’s multi-ministry strategy with industry consultative committees, or the EU’s structured public-private partnerships) show more coherent implementation. Where alignment is lacking, strategies risk falling short: e.g. if academia isn’t incentivized to work with industry or if government efforts aren’t synchronized. Thus, helix governance is a critical determinant of policy success, translating strategic vision into on-the-ground innovation outcomes.

Circular Diamond Profiles of National Innovation Competitiveness

Each region’s STI strategy can be analyzed using an extended Circular Diamond model – which combines Michael Porter’s four determinants of national competitive advantage (factor conditions; demand conditions; related and supporting industries; firm strategy, structure, and rivalry) with two additional dimensions reflecting environmental sustainability and knowledge & innovation cycles. This “circular” diamond emphasizes not only traditional economic competitiveness factors, but also how well an economy regenerates resources and knowledge in a sustainable loop. Below, we compare how the strategies of China, South Korea, India, Qatar, the USA, and the EU strengthen each of these six facets:

1. Factor Conditions (Resources & Talent)

This refers to the quality of a nation’s inputs to innovation – human capital, research infrastructure, financial capital, and data/IT resources. All six actors prioritize factor development, but with nuances:

China

China has massively expanded its R&D infrastructure and talent base. Its strategy to “strengthen original innovation” entails heavy investment in universities, national labs, and basic research funding. China now spends over 2.4% of its GDP on R&D (with a plan to reach 3%+), and as noted earlier it leads the world in patent filings. The government also creates enabling data infrastructure – for example, building a “secure national integrated data market” to ensure abundant data for AI development. A possible weakness is quality: the strategy acknowledges need for “long-term, stable support” for fundamental research to produce truly groundbreaking innovation, moving beyond the quantity metrics.

South Korea

South Korea already has excellent factor conditions in certain respects (world-class universities, one of the highest R&D/GDP ratios ~4.8%, strong STEM workforce). Its Master Plan focuses on sustaining and improving these: addressing the “decreasing research population” via talent programs, and enhancing research environments (e.g. 10-year grants for researchers, sharing of equipment and data nationally to maximize use). Korea is also injecting funds into new strategic fields like space and biotech to build infrastructure there. A “mission-oriented R&D system” suggests allocating resources to key missions (such ashas historically underinvested in R&D (~0.7% of GDP) and faces“mission-oriented R&D system” carbon neutrality or chip leadership). Overall, Korea’s strategy is to maintain its factor strength by focusing resources (preventing dilution) and by bringing in needed foreign expertise (as discussed under human capital).

India

India has historically underinvested in R&D (~0.7% of GDP) and faces infrastructure gaps. The STI policy directly tackles this by proposing significant financing reforms. Every ministry and state must allocate a fixed STI budget, doubling central R&D spending in 5 years, and setting up an STI Development Bank for long-term innovation funding. These steps aim to expand financial and physical research infrastructure. India’s huge human resource potential is being cultivated through education and skill initiatives (as mentioned, aligning with NEP 2020, and creating new research centers of excellence). Additionally, India is improving its Adigital infrastructure (the Digital India program has brought broadband to villages, which the AI strategy notes as key for broad AI adoption). The factor conditions in India’s strategy emphasize inclusion – ensuring even smaller institutions and states build capacity, thus broadening the base of innovation.

Qatar

Qatar with abundant financial capital from energy exports, is translating that into knowledge infrastructure. It has invested billions into state-of-the-art research facilities (like Sidra Medical Research Center, Qatar Computing Research Institute) and into education (branch campuses). The QRDI 2030 outlines enabling elements: “RDI Funding” – creating a balanced public-private funding mix, “RDI Information Systems” – to better share knowledge resources, and “RDI Governance/Regulation” – to make the environment attractive for research talent and capital. Qatar’s small population means human capital is its scarcest factor; the strategy mitigates this by attracting foreign talent and upskilling citizens. It also focuses on niche excellence (e.g. specialized labs for LNG technologies, given its energy sector). Data and computing infrastructure are being addressed via initiatives like a national cloud and plans for data-sharing diplomacy. In summary, Qatar’s factor strategy is to convert wealth into intellectual capital and modern facilities, while partnering internationally to augment its limited human resources.

United States

The USA continues to enjoy extreme factor conditions – top universities, deep capital markets, large pools of data (due to its big digital economy), etc. U.S. strategy documents stress keeping this edge: for instance, the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 not only funds chip fabs but also authorizes significant increases for NSF and NIST to enhance research capacity nationwide. There’s an effort to build manufacturing institutes (public-private centers for advanced manufacturing R&D) to update the physical infrastructure for innovation. The AI R&D Strategic Plan emphasizes ensuring computing resources for researchers (like shared AI testbeds) and expanding the AI-ready workforce. Moreover, American venture capital remains a critical factor input, and policies generally aim to encourage investment (through R&D tax credits, SBIR grants, bridging startups, etc.). The main challenges noted are talent shortages in specific fields (hence immigration reforms and STEM education boosts). But overall, U.S. factor conditions are robust, and policy is more about fine-tuning (e.g., increasing diversity in STEM, ensuring rural broadband, safeguarding research from foreign IP theft) than building from scratch.

European Union

The EU, across its members, possesses strong factor endowments in science (many excellent universities, skilled labor), but faces fragmentation and variation (R&D intensity ranges from ~0.5% to 3% of GDP across countries). The EU’s strategy tries to aggregate and elevate these factors: Horizon Europe provides a €95 billion collective research fund to supplement national investments, thereby creating large-scale projects none could do alone. The EU also invests in pan-European infrastructures – e.g. the EUROHPC initiative builds supercomputing centers accessible to all members, and ESA (European Space Agency) gives Europe shared space tech capacity. A flagship move to improve factors is the plan to train 20 million ICT specialists by 2030 and to have 80% of adults with basic digital skills (Digital Compass goals), directly addressing human capital needs. Financially, the EU is encouraging venture funding and integration of capital markets (traditionally a weak spot compared to U.S. VC availability). Additionally, recognizing data as a key resource, the EU is implementing the European Data Strategy to create common data spaces across sectors (while respecting privacy under the GDPR) – this is intended to improve the quantity and quality of data available for innovation in Europe (a factor critical for AI). In summary, the EU strategy for factor conditions is about scale and cohesion: pooling resources to act as one extensive innovation system and uplifting weaker regions through structural funds so that factor conditions are more uniformly strong across the Union.

2. Demand Conditions

Sophisticated and large local demand can spur innovation by giving firms an incentive to meet high standards and tailor products early. Each region’s approach to stimulating demand for innovation differs:

China

With 1.4 billion people and a growing middle class, China’s domestic market is a huge demand pull. The government actively leverages this: for example, public procurement and industrial policy favor domestic tech solutions (e.g. requiring government offices to use local software, which nurtures domestic IT firms). The strategy of “promoting deep integration between scientific and industrial innovation” and “accelerating the transformation and application of major S&T achievements” is essentially about turning research into products that meet market needs quickly. The mention of “boosting…Digital China initiative” and widespread AI adoption (with “AI Plus” penetrating key industries like manufacturing, finance, healthcare) indicate that China is pushing demand across sectors by incentivizing traditional industries to digitize and adopt AI. Additionally, Chinese consumers are often open to new tech (e.g. mobile payments, super apps), giving companies a large testbed. The New Generation AI Plan even set targets for AI usage in domestic public services. Thus, China’s strategy uses policy (like smart city programs, autonomous vehicle pilot zones) to cultivate home-market demand that gives Chinese innovators scale and experience before venturing abroad.

South Korea

Korea’s relatively smaller market (51 million people) is highly tech-savvy, providing a good environment for early adoption. The government’s AI strategy explicitly includes making “all industries” adopt AI and creating a “next-generation intelligent government” as a lead user. This dual approach – private sector adoption and government as model user – drives demand. For instance, Korea’s “Smart Factory” initiative prompted thousands of SMEs to implement IoT/AI solutions, spurred by government incentives. Demand is also bolstered by setting high standards (Korean consumers expect top-notch connectivity and devices – recall Korea’s early 5G rollout, which pushed telecom firms and device makers to innovate). Moreover, Korea leverages global demand in niche areas: e.g. it aims to be the world’s top AI chip provider for data centers, meaning it’s anticipating foreign demand and aligning domestic R&D to that. Domestically, cultural acceptance of new tech (e.g. delivery robots, digital banking) is strong, and the government nurtures that with public education on AI and some welfare AI solutions, to ensure society pulls innovation (people want it) as much as companies push it. Summarily, Korea’s demand conditions are enhanced through policy-orchestrated adoption programs and a populace eager for innovation – creating a virtuous cycle for companies like Samsung, LG, Naver to constantly develop advanced offerings for discerning local users.

India

India’s large population offers potentially huge demand, but low average incomes and varied regional needs make it a challenging market. The AI strategy notes that government must often drive initial adoption in sectors like agriculture and healthcare because private sector alone finds it not immediately profitable. Accordingly, the government has launched Digital India initiatives (e.g. building digital ID, digital payments which then enabled a boom in fintech innovation driven by citizen uptake). India’s STI approach to demand is twofold: identifying key areas of societal need where tech can have “the greatest externalities” (positive spillovers) – such as AI in agriculture (e.g. crop yield prediction systems for farmers) or healthcare (telemedicine for rural areas) – and then investing or partnering to implement solutions there; and raising the quality bar via standards and regulations in emerging sectors (for example, India is developing its own standards for drone safety, which pushes local drone startups to meet them and become globally competitive). The sheer size of India’s internal markets in sectors like telecom (over a billion mobile subscribers) also allows local firms to achieve scale – e.g. Reliance Jio’s 4G network rollout created demand for affordable smartphones and spurred domestic electronics assembly. Another example: the government’s push for electric vehicles has come through measures like the FAME subsidy scheme, which is now stimulating demand for EVs and in turn local manufacturing of EV components. However, India’s demand conditions can be hampered by limited purchasing power and infrastructural gaps. The STI policy is trying to improve that by inclusive innovation – making products extremely affordable (frugal innovation) to unlock mass demand, and by improving infrastructure (e.g. expanding broadband, power, etc.) so that more of the population can be active digital consumers. In essence, India’s strategy acknowledges demand won’t automatically rise to cutting-edge tech unless the state intervenes as a catalyst and enabler, bridging the gap until the private market matures enough to sustain itself.

Qatar

As a wealthy country with a small population (~3 million, mostly expatriates), Qatar’s domestic demand for high-tech products is niche but present – e.g. demand for smart city solutions in Doha, or advanced healthcare for its residents. The government often acts as the chief orchestrator of demand: for instance, it implements smart infrastructure (stadiums with IoT, government e-services with AI chatbots) thereby becoming the lead customer for new tech. The Qatar Digital Government initiative and the TASMU Smart City project create local markets for digital innovations in transport, logistics, health, and environment. Qatar’s AI strategy also envisions making the country a testbed where new AI solutions can be developed and then exported – the idea of “Qatar as an AI+X nation that others look up to”implies using domestic deployments (in education, business, government) to showcase what AI can do, thus generating both local and international demand. Another angle is international demand capture: Qatar encourages foreign tech firms and start-ups to establish presence in Qatar (e.g. through attractive business regulations in zones like QSTP). By doing so, Qatar imports demand – i.e. those companies bring projects and services that increase local innovation activity. Additionally, Qatar’s affluent consumer base can serve as early adopters for technologies like electric vehicles, luxury tech products, etc., though this is a small market. In summary, Qatar’s demand-side strategy is government-led – creating demonstration projects and living labs that generate a pull for innovation – with an eye to leveraging those successes to tap into global demand (especially in Gulf and emerging markets where Qatar could export its proven solutions in, say, desalination AI or sports tech after the World Cup experience).

United States

U.S. demand conditions are among the world’s most favorable to innovation: a large, wealthy market with consumers and businesses that enthusiastically adopt new technologies. The U.S. government generally doesn’t need to force demand in the private sector – instead, it often plays a role in setting aspirational goals and letting market forces respond. For example, the announcement of a nationwide EV charging network and future gasoline car phase-out by states like California sends a demand signal to automakers to innovate in EVs. The U.S. government is a massive buyer as well (federal procurement ~ $600B/year), and it uses that to create demand for innovation: e.g. the DoD’s contracts for SpaceX essentially helped create a new space launch market, and more recently, government commitments to purchase “American-made” clean technologies (like heat pumps, green steel) under climate initiatives aim to stimulate those nascent markets. Another mechanism is standards and regulations – for instance, the EPA’s tightening of emissions standards in vehicles pushed companies to innovate in fuel efficiency and now electrification. Consumers in the U.S. often set global trends (everyone wanted a smartphone after U.S. adoption soared). Importantly, the diversity of the U.S. market allows early adopters to form niche demands that grow – for instance, tech-savvy segments in Silicon Valley try new apps and devices, providing test markets. The U.S. also has strong venture capital which not only supplies funds (factor) but also pushes startups to achieve product-market fit, essentially ensuring they meet some demand. One area the U.S. strategy identifies to boost demand is infrastructure modernization – by deploying advanced infrastructure (smart grids, 5G, etc.), it creates platforms on which new services can be built and demanded. Additionally, American culture’s receptiveness to innovation (though tempered by recent privacy and ethical concerns) traditionally means if you build a better mousetrap, people will beat a path to your door – a healthy demand scenario. Summing up, U.S. policies focus on enabling conditions (e.g. antitrust to keep markets competitive, consumer protection to build trust in new tech, and sometimes subsidies to lower cost for first buyers) rather than direct government programs to adopt tech (except in defense and space). One exception is healthcare: the government via agencies like HHS is trying to spur demand for health IT and telehealth, as the private U.S. healthcare market has inefficiencies.

European Union

The EU has a large single market (~450 million people) with sophisticated demand shaped by high standards – often called the “Brussels effect” because EU regulations (on safety, environment, etc.) effectively set global benchmarks that companies innovate to meet. The EU’s strategy explicitly uses this as a lever: by aligning AI policy and preventing fragmentation, the EU wants to ensure a “first-mover advantage” in adoption of AI technologies. This includes coordinating public procurement of innovative solutions (e.g. joint procurement of AI systems for public sector across countries) and creating lead markets in areas like green tech (the EU’s Green Public Procurement tells governments to buy eco-innovations, stimulating those industries). European consumers are generally discerning about quality and sustainability, which creates demand for advanced products (like Germany’s demand for precision engineering, or Scandinavia’s demand for clean tech). The EU also fosters demand through pilot programs – for instance, the EU AI Testing and Experimentation Facilities (TEFs) allow companies and users in sectors like agriculture or healthcare to try AI solutions, seeding interest and trust. Another distinctive EU approach is regulatory-driven demand: e.g. banning certain less efficient or unsafe products (like incandescent bulbs, or soon, high-emission vehicles) thereby forces a shift of demand to innovative alternatives (LED lights, electric cars). While sometimes criticized for burdening companies, this method has spurred innovation aligning with those standards (Philips became a leader in LEDs, European automakers invest heavily in EVs to meet CO2 targets). Additionally, the EU tries to unify demand across member states – e.g. through the Coordinated Plan on AI, encouraging each country to roll out AI in public services, education, etc., so that there’s an EU-wide market that startups can scale across. Challenges remain: demand in the EU can be fragmented by language and cultural preferences, and European companies often scale up slower partly due to differences in consumer markets. The New European Innovation Agenda addresses that by aiming to create pan-European sandboxes where innovators can launch across multiple countries easily, thus aggregating demand. In summary, the EU leverages its large market and high standards to shape demand for innovation, and increasingly uses coordination and regulation to make that demand a springboard for its companies (exemplified by its push for “trustworthy AI” – setting rules so that consumers feel safe using AI, which should increase uptake of AI products under those rules).

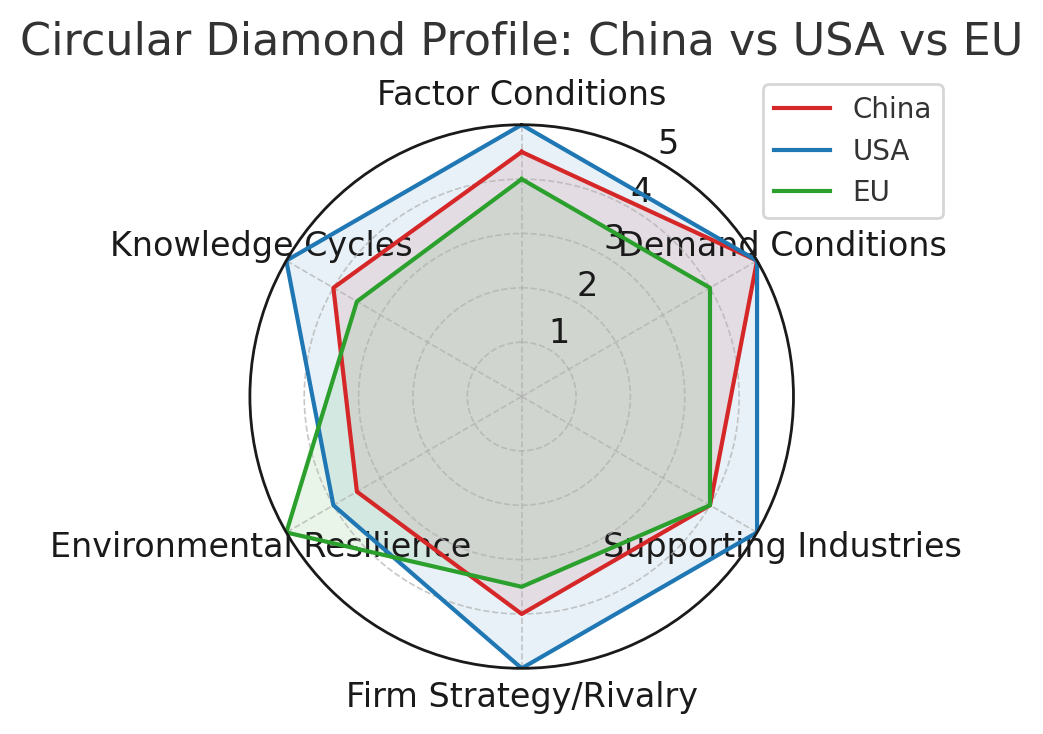

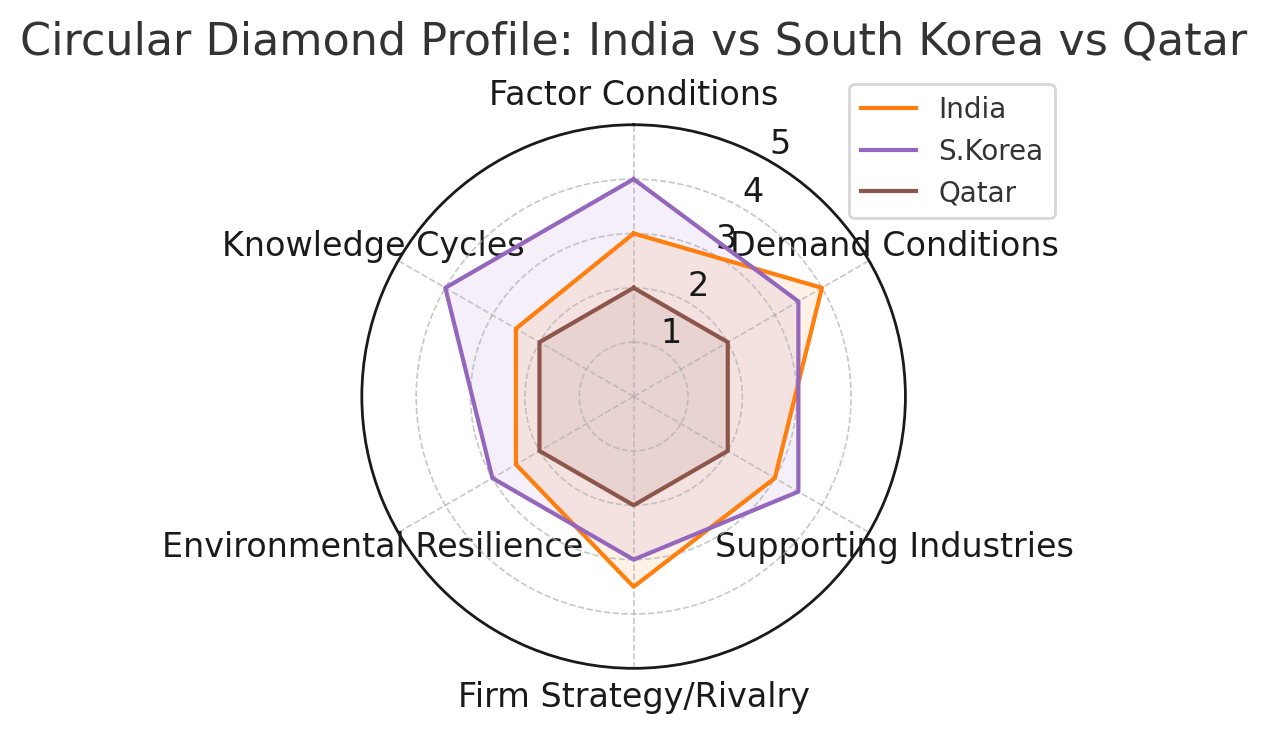

The following radar charts provide a visualization of the Circular Diamond profile for the selected regions, highlighting their relative strengths in each of the six dimensions (values are illustrative, based on qualitative analysis of strategy priorities):

Circular Diamond Profile comparison for China, the USA, and the EU. Each axis represents one dimension (Factor Conditions, Demand Conditions, Supporting Industries, Firm Strategy/Rivalry, Environmental Resilience, Knowledge Cycles). A larger area indicates a stronger strategic emphasis/capability in that dimension. The USA (blue) shows balanced strength, especially in rivalry and knowledge flows; China (red) is strong in demand and factors but slightly less in environmental sustainability; the EU (green) excels in environmental resilience and maintains solid factors and demand, but has a smaller scope in firm rivalry (due to less dynamic startup scaling historically). These profiles reflect strategic focus: e.g., the EU’s deliberate emphasis on sustainability, China’s push for scale and self-reliance, and the USA’s entrenched competitive market system.

Circular Diamond Profile comparison for India, South Korea, and Qatar. India (orange) has improving factor conditions and demand (large market), but still weaker supporting industries and knowledge cycles (silos exist) – the strategy aims to bolster those via industry-academia links and supply chain initiatives. South Korea (purple) is strong in knowledge cycles and factor conditions (thanks to effective education and R&D systems) and is solidifying environmental resilience (carbon-neutral tech drive); its relatively lower demand score reflects market size, which Korea compensates by exporting innovation. Qatar (brown) has high investment (factor) but as a small economy it’s still developing depth in supporting industries and broad firm rivalry – its strategy leans on international linkages to improve those.

3. Related and Supporting Industries

A vibrant network of suppliers, service providers, and complementary industries fosters innovation through clustering effects. Strategies that promote clusters, SMEs, and linkages strengthen this dimension:

China

Recognizing that innovation cannot happen in isolation, China’s policy actively builds industrial ecosystems. For example, in semiconductors, it’s not just funding chip designers, but also upstream equipment makers, downstream assemblers, and establishing entire semiconductor parks. The push for “coordinated development of education, sci-tech and talent” also implies linking academia (as a supporting partner) with industry needs. China’s regional cluster strategy (e.g. Greater Bay Area for tech, Beijing for AI, Wuhan for optics, etc.) concentrates related industries together. It also uses standardization alliances and industry associations to bring companies together to solve common challenges (as seen in 5G, where a lot of Chinese companies and the government worked in tandem to push a homegrown standard). By nurturing not just champion firms but also their suppliers (often via subsidies and local content requirements), China has grown more complete supply chains – for instance, domestic battery makers (CATL) rose alongside the EV industry due to supportive policies linking auto and battery sectors. Additionally, big tech firms are encouraged to develop platforms that support smaller businesses (AliCloud enabling countless start-ups). Overall, China’s strategy creates dense supporting networks – albeit sometimes this means duplication in different provinces racing in the same sector, which the central government is now trying to coordinate better.

South Korea

In the past, Korea’s innovation was heavily centered on chaebols (conglomerates) with less developed supplier SMEs (often Japanese or foreign suppliers). Recent strategy addresses this by strengthening SME innovation and industry linkages. The Master Plan introduced programs like the “five-stage tailored innovation support for business-affiliated research institutes” to upgrade R&D at smaller firms and link them with larger companies. Also, “industry-specific private R&D cooperation committees” are established to ensure industry players and government jointly plan R&D to fill supply chain gaps. For example, after Japan’s export curb on materials in 2019, Korea launched initiatives to develop local chemical and materials suppliers – now it’s seeing a burgeoning of those supporting industries. Tech clusters in Korea (e.g. Pangyo Techno Valley for ICT start-ups, Daedeok Innopolis for research institutes) foster close interaction between related firms, universities, and startups. The innovation policy also encourages spillovers from big firms: large companies are nudged to open their procurement to startups (so a Samsung might incubate component suppliers). The concept of “Regional Innovation” in the plan – each province having R&D hubs for its focus industries– further bolsters local supporting networks (e.g. a machinery hub in Busan, biotech hub in Daejeon, etc.). In sum, Korea is moving from a top-heavy industrial structure to a more networked one, with policy bridging chaebols and SMEs, and promoting ancillary industries (such as the government-backed automotive parts clusters now transitioning to make EV parts).

India

India’s supporting industry networks are patchy – there are some strong clusters (Bangalore for IT, Pune for auto, Hyderabad for pharma-biotech) but also large parts of the economy not well integrated into innovation supply chains. The STI policy addresses this by fostering clusters and technology parks. There are proposals for Science & Technology “City” clusters in major metros to bring research institutions, industries, and start-ups together. The government also supports Sectoral Innovation Councils in areas like fintech, biotech, etc., to align industry and academia efforts. For MSMEs, the Innovation policy and Startup India campaign provide networking platforms (e.g. the Startup Hub connects entrepreneurs with mentors, corporates, and investors). In manufacturing, the Production-Linked Incentives (PLI) schemes (outside the STI policy but aligned in spirit) are creating entire ecosystems – e.g. in electronics, PLI incentives have drawn not just assemblers like Foxconn, but also component makers to set up in India, thereby building a local supply network. Moreover, India is leveraging its big IT services sector to support other industries’ innovation – IT firms partner with, say, agriculture start-ups to provide tech backbone (like TCS supporting agritech incubators). An interesting supporting industry angle is traditional industries and crafts: the STI policy wants to integrate traditional knowledge systems with modern innovation, which could mean boosting rural artisan clusters with design/marketing innovation, connecting them to global markets (this improves socio-economic impact and sustains diverse supporting sectors). Challenges remain in fragmentation and coordination (the policy highlights the need for better “interconnectedness and collaboration” among different stakeholders). But initiatives like setting up Common Research and Technology Development Hubs (CRTDHs) for MSMEs in various sectors, and large missions (e.g. clean energy mission bringing together coal, renewable, auto industries for storage tech) are steps toward a more integrated supporting industry fabric.

Qatar

Given its narrow economic base historically (dominated by oil & gas), Qatar is essentially building supporting industries from scratch in its diversification journey. The QRDI strategy’s focus on five priority areas (Energy, Health, Sustainability, Society, Digital) is meant to concentrate efforts and create critical mass in those domains, with each priority bringing together multiple players. For example, in Energy, they encourage not just core oil/gas companies but also new firms in solar, carbon capture, and related engineering services to cluster in initiatives like Energy Hub at Education City. The Qatar Science & Technology Park (QSTP) is a classic cluster initiative where multinational tech companies, Qatari start-ups, and research institutes co-locate and collaborate (e.g. QSTP houses a tech venture fund, innovation labs, and offices of companies like Microsoft, creating a micro-ecosystem). Qatar also uses partnerships as a way to import supporting industries – inviting foreign universities or companies to set up R&D and incubators means they bring their supplier networks and expertise, which then local entrepreneurs can tap into. There is a drive for local supplier development in sectors like defense and healthcare, often through offset programs (foreign suppliers investing in local startups or training as part of contracts). A notable supporting sector Qatar is cultivating is ICT – through its digital agenda, it hopes to foster a domestic tech sector that can support all other industries via solutions (for example, a homegrown cybersecurity industry to support finance and government sectors). These efforts are nascent; Qatar’s innovation ecosystem is still small, so a few anchor institutions (like Qatar Foundation, and big state enterprises) play outsized roles in mentoring and supporting smaller firms. Over time, success would be a scenario where, say, a Qatari medical device startup finds local component suppliers and service providers, but currently many such inputs are imported. The strategy acknowledges this and hence emphasizes international research collaborations and knowledge transfer to seed local supporting industries.

United States

The U.S. has historically benefitted from extremely well-developed supporting industries across almost every sector. Silicon Valley is the textbook example: a dense network of suppliers (hardware, software, legal, VC, talent) supporting each other and spawning continuous innovation. U.S. policy typically doesn’t need to create clusters – they emerge and flourish organically due to market forces and prior public investments (like the internet, or the biotech clusters around NIH-funded university labs). However, recognizing some hollowing out in manufacturing supply chains (offshoring), recent policies aim to rebuild certain supporting industries domestically for resilience – e.g. initiatives to encourage domestic production of pharmaceutical ingredients (so biotech innovation isn’t entirely dependent on foreign suppliers), or the CHIPS Act funding not just chip fabs but also suppliers of semiconductor chemicals and tools to come to the U.S. (recreating a fuller local ecosystem). Additionally, the Manufacturing USA network (14 innovation institutes) explicitly connects large manufacturers, small suppliers, and academic experts in fields like 3D printing and robotics, to accelerate diffusion of new techniques among supporting firms. On a regional level, the Economic Development Administration runs Build Back Better Regional Challenge grants to boost innovation clusters in distressed areas (supporting industry development in places beyond the coasts). Moreover, U.S. antitrust policies historically ensured no single firm could dominate supply chains end-to-end, thus encouraging a competitive supplier base – this continues (though big tech’s ecosystem control is a new challenge). Another strength: robust professional services (consulting, design, marketing, VC, etc.) which support innovators – these flourish in the U.S. environment and are part of supporting industries that get less attention but are crucial. In summary, the U.S. strategy doesn’t explicitly focus on “supporting industries” because they are largely present – the focus is more on keeping them healthy through measures like SME support loans, R&D tax credits that small suppliers can use, etc. One area receiving new attention is workforce training as a supporting factor for industry – e.g. apprenticeships in advanced manufacturing to ensure skilled trades are available to support high-tech production.

European Union

The EU’s approach to supporting industries often involves cross-border clusters and industrial alliances. Recognizing that no single country might cover a whole value chain, the EU sponsors Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) – for instance, one on Batteries and one on Microelectronics – which bring together dozens of firms and research orgs from multiple countries to develop an entire supply chain (from materials to assembly) in Europe. This is directly aimed at building a complete ecosystem in sectors deemed strategic. EU regional policy also has the concept of “Smart Specialisation” – each region identifies sectors where it has strengths and the EU supports cluster development there, avoiding duplication. So, say, clusters for photonics in Eindhoven or nanotech in Leuven get EU backing and are networked with similar hubs. Moreover, the EU’s Horizon Europe program encourages creation of pan-European innovation networks: e.g. the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) runs Knowledge and Innovation Communities (KICs) in climate, health, etc., which link corporations, universities, and SMEs across Europe to share knowledge and supply chain opportunities. The EU also actively sets standards (like for 5G, advanced manufacturing interoperability etc.) that unify the requirements for supporting industries. A standout aspect is SME support: programs like Enterprise Europe Network help small companies find partners and customers across the single market – effectively broadening their supporting ecosystem beyond their home country. The EU also fosters open innovation platforms (for example, FIWARE for IoT, initiated by EU to provide common architecture so supporting software firms can easily integrate). In sum, the EU strategy is to knit together the diverse national industrial bases into cohesive European supporting industries, using funding consortia and legal frameworks. One challenge is aligning different national interests (e.g. French vs German preferences in industrial standards), but the coordinated AI plan and others show progress – aligning on AI “sandboxes” and data spaces is meant to ensure an AI startup in one country can easily scale and find customers/suppliers EU-wide rather than face 27 fragmented markets.

4. Firm Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry

This aspect examines how companies are organized and compete domestically. Do policies encourage competitive, innovative behavior by firms or protect certain incumbents? Are entrepreneurship and new entrants fostered?

China

For decades, China followed a model of state-guided but increasingly competitive markets. Its STI strategy still involves guiding firm strategy through industrial policy (e.g. setting target sectors, providing subsidies to certain firms, encouraging mergers in some fields for scale). That said, internal rivalry in many tech sectors is fierce – Chinese tech giants (Alibaba vs. Tencent, etc.) compete intensively, often spurred by overlapping government support. The government has also promoted a wave of start-ups and SMEs – the slogan “Mass Entrepreneurship and Mass Innovation” led to incubators and VC funds popping up nationwide. As a result, China produces a huge number of start-ups and unicorns. However, the state does intervene to align firm behavior with national objectives (recent regulatory crackdowns on fintech and ed-tech, for example, reined in certain sectors to redirect talent toward “hard tech” like chips). So the rivalry exists, but within bounds set by the government’s priorities. The structure of industries often involves a few national champions plus a competitive fringe. In telecom, for instance, Huawei and ZTE were nurtured to become global champions, but they still compete with each other and numerous smaller firms. The new strategy explicitly notes “reinforcing the role of enterprises as key players in innovation” and improving things like IP protection to encourage firm-level innovation. This is a shift from past reliance on public research institutes. It also includes tax incentives (R&D super-deduction) to push firms to invest in innovation. So China is trying to emulate aspects of a competitive market economy to drive innovation, but without letting go of strategic control. The outcome is a somewhat unique ecosystem where entrepreneurship thrives (many private start-ups) yet simultaneously the state and party have influence in firm decisions (through mechanisms like Communist Party committees in companies, or state-owned venture funds). If the balance is kept, this can produce world-leading firms (as seen in renewable energy where dozens of Chinese companies compete, driving costs down). But if state control stifles competition too much, innovation could suffer – an issue Chinese policymakers are mindful of, hence they’ve let internet and consumer tech competition flourish until recently, and are now channeling it to new sectors (e.g. encouraging rivalry in semiconductors by funding multiple firms rather than just one).

South Korea

Historically dominated by conglomerates (chaebols), Korea’s competitive landscape has been oligopolistic in many industries. While this led to strong global firms (Samsung, Hyundai), it also meant less room for SMEs and start-ups. The current innovation strategy is trying to diversify the entrepreneurship mix: for example, by supporting “deep tech start-ups” through incubators and a government-backed venture fund-of-funds, and by reforming regulations to make it easier for new businesses (Korea has been cutting red tape and offering sandboxes for fintech, etc.). There is also a cultural shift underway to celebrate venture success (beyond the traditional path of chaebol employment). That said, large firms are still central – but the government encourages them to be more innovative and globally oriented (the national AI strategy expects even conglomerates to embed AI and compete on that front). Rivalry in the domestic market is moderate – in sectors like telecom or banking there are few players, but in consumer electronics or cars, the main rivalry is on global markets (Samsung vs Apple, Hyundai vs Toyota, etc.). The Korean government often played a coordinating role among firms (preventing excessive duplication, fostering cooperation in pre-competitive research). However, the innovation plan stresses market-driven innovation a bit more than older plans, aiming to make the private sector the leader of the innovation ecosystem. They’ve set up an innovation score system to tailor support to firms that innovate, rewarding performance. One structural change is promoting spin-offs – e.g. letting researchers from chaebols start their own companies or encouraging big firms to invest in start-up accelerators. South Korea’s relatively hierarchical corporate culture is slowly adapting to the more agile, open innovation models. The government’s role remains significant in shaping industry structure (it can convene partnerships or push companies into consortiums), but competition policy in Korea has also strengthened (antitrust enforcement on chaebols to encourage fair competition for SMEs). So the trajectory is toward a more level playing field while leveraging the strength of big firms – ideally achieving a complementary dynamic where startups innovate and chaebols scale those innovations globally.

India

India’s firm landscape is bifurcated: on one hand a few big conglomerates in areas like petrochemicals, IT services, and an enormous number of micro-entrepreneurs and SMEs on the other, with a growing cohort of tech start-ups in between. The STI and AI strategies strongly push entrepreneurship and start-ups as the future. Initiatives like Startup India (with easier compliance, funding support, incubation networks) and Atal Innovation Mission (setting up incubators, tinkering labs) have catalyzed thousands of new start-ups. India now has over 100 unicorns (many in e-commerce, fintech, SaaS), indicating a healthy startup rivalry. The government encourages this competition by opening more sectors to private players (e.g. space launch sector, drones, coal mining – areas once only for state entities). Another focus is on grassroots entrepreneurs: the STI policy explicitly talks about fostering “S&T-enabled entrepreneurship at grassroots”, simplifying IP filing for them, providing fellowships and challenge grants. This is to tap innovation beyond big cities. On the other side, some national champions are being favored in strategic fields – e.g. India identified key “Strategic Sectors” where a few large firms (possibly domestic champions) would be supported to scale (like an electronics manufacturing champion, a telecom equipment champion). But even those sectors are open to private competition (if multiple Indian firms want to compete in chip fabrication, they can all get incentives). The structure of Indian industry is also influenced by family-owned business groups and a legacy of state-owned enterprises; reforms are pushing many SOEs to privatize or become more efficient to allow private competition (e.g. in defense production, new licenses have been given to private companies for ammunition, ending the ordnance factory monopoly). In summary, India’s strategy works to create a vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem – simplifying regulations (like scrapping a rule that required permits for geospatial data, which unlocked a wave of GIS start-ups), improving ease of doing business, and nurturing incubators/accelerators in every state. The cultural attitude towards failure in business is gradually changing with government campaigns encouraging risk-taking. Still, hurdles remain: infrastructure and bureaucratic delays can hamper new firms, and cronyism can sometimes shield incumbent big players. The hope is that by shining policy spotlight on innovation and explicitly valuing start-ups (through awards, procurement preferences for innovative SMEs, etc.), the competitive dynamic will tilt towards innovation rather than rent-seeking.

Qatar